Iowa Gambling Task Bechara 1994

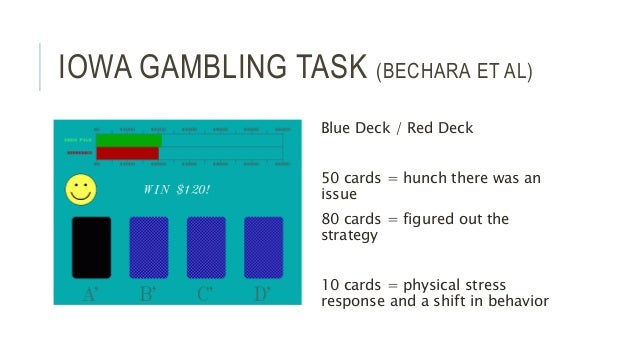

A decision task designed to simulate real-life decision-making. On each trial the decision maker chooses a card from one of four decks, each choice resulting in a fixed gain of $100 for any card from two of the decks or $50 for any card from the other two, although the decision maker is not told this. For some cards, the decision maker also suffers a loss. Losses total $1,250 for every ten cards in two of the decks and $250 for every ten cards in the other two. These gains and losses are arranged so that two of the decks yield substantial expected losses and the other two substantial expected gains over every run of 10 cards, but there are sharp differences between short-term and long-term payoffs, small losses occurring relatively frequently in some decks and larger but less frequent losses occurring in others. The task was introduced by the Canadian neuroscientist Antoine Bechara (born 1961) and published with three colleagues in the journal Cognition in 1994, where it was shown that people with damage to the prefrontal cortex, in contrast to neurologically undamaged participants in their control group, performed badly, failing to consider the future consequences of their actions and being guided only by immediate prospects. See also somatic marker hypothesis. IGT abbrev. [So-called because the researchers who developed it were at the University of Iowa at the time]

One way Damasio demonstrated the effects of somatic markers was through the Iowa gambling task (e.g., Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, & Anderson, 1994). In this task, participants are presented with four decks of cards and instructed to choose a card from any of the decks.

The Iowa gambling task (IGT) is a psychological task thought to simulate real-life decision making.It was introduced by Antoine Bechara, Antonio Damasio, Hanna Damasio and Steven Anderson,[1] then researchers at the University of Iowa. It has been brought to popular attention by Antonio Damasio (proponent of the somatic marker hypothesis) in his best-selling book Descartes' Error.[2]

The task was originally presented simply as the Gambling Task, or the 'OGT'. Later, it has been referred to as the Iowa gambling task and, less frequently, as Bechara's Gambling Task.[3] The Iowa gambling task is widely used in research of cognition and emotion. A recent review listed more than 400 papers that made use of this paradigm.[4]

Task structure[edit]

Participants are presented with four virtual decks of cards on a computer screen. They are told that each deck holds cards that will either reward or penalize them, using game money. The goal of the game is to win as much money as possible. The decks differ from each other in the balance of reward versus penalty cards. Thus, some decks are 'bad decks', and other decks are 'good decks', because some decks will tend to reward the player more often than other decks.

- Humans: the Iowa Gambling Task 1.1 Developing a simulation of real-life decision-making When it was designed by Bechara and colleagues in the early 90s (Bechara et al., 1994), the IGT was meant to be a tool to specifically test impairements of decision-making in a controlled labo-ratory setting.

- The Iowa gambling task (IGT; Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, & Anderson, 1994) is a popular neuropsychological paradigm used to assess decision-making deficits in clinical popula-tions. The IGT was originally developed to detect decision-making deficits of patients with lesions to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), but in the last two decades.

Iowa Gambling Task Purchase

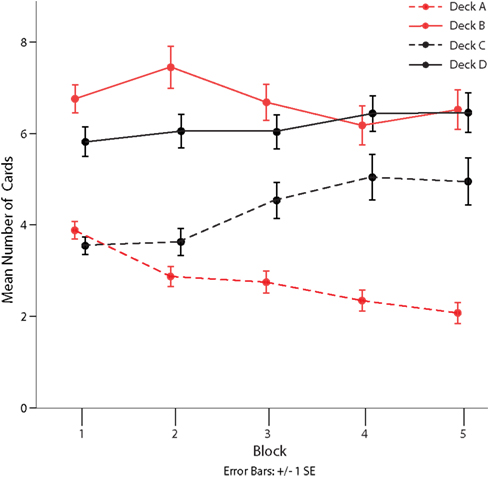

Common findings[edit]

Most healthy participants sample cards from each deck, and after about 40 or 50 selections are fairly good at sticking to the good decks. Patients with orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) dysfunction, however, continue to persevere with the bad decks, sometimes even though they know that they are losing money overall. Concurrent measurement of galvanic skin response shows that healthy participants show a 'stress' reaction to hovering over the bad decks after only 10 trials, long before conscious sensation that the decks are bad.[5] By contrast, patients with amygdala lesions never develop this physiological reaction to impending punishment. In another test, patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) dysfunction were shown to choose outcomes that yield high immediate gains in spite of higher losses in the future.[6] Bechara and his colleagues explain these findings in terms of the somatic marker hypothesis.

The Iowa gambling task is currently being used by a number of research groups using fMRI to investigate which brain regions are activated by the task in healthy volunteers[7] as well as clinical groups with conditions such as schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Critiques[edit]

Although the IGT has achieved prominence, it is not without its critics. Criticisms have been raised over both its design and its interpretation. Published critiques include:

- A paper by Dunn, Dalgliesh and Lawrence[4]

- Research by Lin, Chiu, Lee and Hsieh,[8] who argue that a common result (the 'prominent deck B' phenomenon) argues against some of the interpretations that the IGT has been claimed to support.

- Research by Chiu and Lin,[9] the 'sunken deck C' phenomenon was identified, which confirmed a serious confound embedded in the original design of IGT, this confound makes IGT serial studies misinterpret the effect of gain-loss frequency as final-outcome for somatic marker hypothesis.

- A research group in Taiwan utilized an IGT-modified and relatively symmetrical gamble for gain-loss frequency and long-term outcome, namely the Soochow gambling task (SGT) demonstrated a reverse finding of Iowa gambling task.[10] Normal decision makers in SGT were mostly occupied by the immediate perspective of gain-loss and inability to hunch the long-term outcome in the standard procedure of IGT (100 trials under uncertainty). In his book, Inside the investor's brain,[11]Richard L. Peterson considered the serial findings of SGT may be congruent with the Nassim Taleb's[12] suggestion on some fooled choices in investment.

References[edit]

- ^Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., Anderson, S. W. (1994). 'Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex'. Cognition. 50 (1–3): 7–15. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(94)90018-3. PMID8039375.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^Damasio, António R. (2008) [1994]. Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. Random House. ISBN978-1-4070-7206-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)Descartes' Error

- ^Busemeyer JR, Stout JC (2002). 'A contribution of cognitive decision models to clinical assessment: Decomposing performance on the Bechara gambling task'. Psychological Assessment. 14 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.14.3.253.

- ^ abDunn BD, Dalgleish T, Lawrence AD (2006). 'The somatic marker hypothesis: a critical evaluation'. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 30 (2): 239–71. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.07.001. PMID16197997.

- ^Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR (1997). 'Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy'. Science. 275 (5304): 1293–5. doi:10.1126/science.275.5304.1293. PMID9036851.

- ^Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR (2000). 'Characterization of the decision-making deficit of patients with ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions'. Brain. 123 (11): 2189–2202. doi:10.1093/brain/123.11.2189. PMID11050020.

- ^Fukui H, Murai T, Fukuyama H, Hayashi T, Hanakawa T (2005). 'Functional activity related to risk anticipation during performance of the Iowa Gambling Task'. NeuroImage. 24 (1): 253–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.028. PMID15588617.

- ^Lin CH, Chiu YC, Lee PL, Hsieh JC (2007). 'Is deck B a disadvantageous deck in the Iowa Gambling Task?'. Behav Brain Funct. 3: 16. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-3-16. PMC1839101. PMID17362508.

- ^Chiu, Yao-Chu; Lin, Ching-Hung (August 2007). 'Is deck C an advantageous deck in the Iowa Gambling Task?'. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 3 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-3-37. PMC1995208. PMID17683599.

- ^Chiu, Yao-Chu; Lin, Ching-Hung; Huang, Jong-Tsun; Lin, Shuyeu; Lee, Po-Lei; Hsieh, Jen-Chuen (March 2008). 'Immediate gain is long-term loss: Are there foresighted decision makers in the Iowa Gambling Task?'. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 4 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-4-13. PMC2324107. PMID18353176.

- ^Richard L. Peterson (9 July 2007). Inside the Investor's Brain: The Power of Mind Over Money. Wiley. ISBN978-0-470-06737-6.

- ^'Nassim Nicholas Taleb Home & Professional Page'. www.fooledbyrandomness.com.

Iowa Gambling Task Bechara 1994 Episode

External links[edit]

Iowa Gambling Task Bechara 1994 Full

- A free implementation of the Iowa Gambling task is available as part of the PEBL Project. For free, you will need to contribute to the WIKI, financially, software development, or publish and cite the program.

- A customizable version of the web implementation that works with Google Spreadsheets (your own spreadsheet) is here.

- A free implementation for Android and iPad.